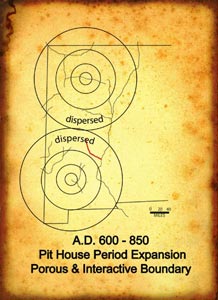

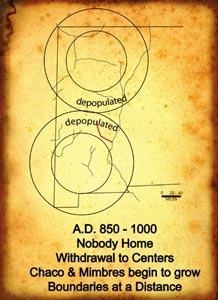

The current interpretive narrative for the pueblo history of the Cañada Alamosa begins in the 7th and 8th centuries. The pithouse village on the Victorio Site appears to be an outlier reflecting strong ties to the southern pueblo area where the most densely populated areas are on the major drainages. The frontier between north and south is wide and sparsely populated. This continues almost until the end of the ninth century. Then, for the next hundred years or so, no one appears to be home on the Cañada Alamosa. Perhaps the forces at the dual centers of culture were pulling in the populations from the periphery in the same way that a plant gathers its nutrients before flowering.

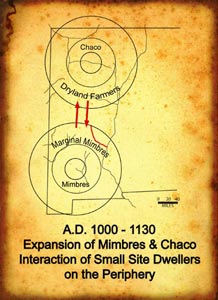

The fluorescence came, of course. By the 11th century Chaco to the north and Mimbres to the south were playing major roles. But these were very different centers. Chaco was a center for trade while Mimbres was a center for production. The Chacoan center controlled products from a range of production areas, many of them dependent on dry land farming. The Mimbres Valley was the center of agricultural production in the south and the two major adjacent drainages were filled with like-minded farmers. During the 11th century the Cañada Alamosa was home to marginal farmers and Mimbres affiliates who occasionally traded with dispersed small sites of northern groups affiliated with the Chaco system to the north. Thus the Cañada Alamosa region was a porous and interactive boundary between small villages of dry land farmers and occasional gatherers who lived on the edge of both systems.

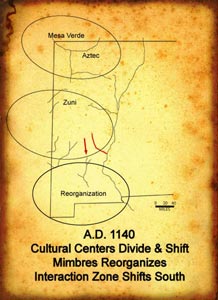

By A.D. 1130, a prolonged drought forced the collapse of both the Chaco and Mimbres systems, leaving those on the peripheries to figure it out for themselves. What happened to the local Cañada Alamosa groups is unclear. Nelson's model, based on extensive work on the Ladder Ranch, suggests that Mimbres affiliates two canyons to the south adopted a mobile small site approach. What is interesting is that the dry land farmers from the north immediately came south in small communities. Thus, it was probably equally attractive to those on the edge of the Mimbres world. Perhaps they joined forces, the data are not yet clear. What is clear is that the dry land farmers from the north saw the regular waters of the Cañada Alamosa as a refuge. And so they came in little groups, bringing with them their traditional ceramic assemblages, their architectural styles and their sense of who they were. The move provided definition for the new cultural area that would revolve around Zuni. There is currently little evidence for assimilation or incorporation of local Mimbres affiliates, although with the collapse of Mimbres ceramic production, such a process would be very difficult to see.

By the middle 1100s the canyon was well populated as evidenced by the extensive pattern of small farming villages. By 1200, the population had aggregated into one community, the Victorio Site. But this time their allegiance was to not either of the old central places. The Victoro Site had become the southeastern most Tularosa Phase pueblo in a system that revolved around Zuni and extended well beyond the Arizona/NM border. To the south the old Mimbres world was reforming in an extensive system of adobe pueblos and was linking itself to the new central place of Casas Grandes in northern Mexico.

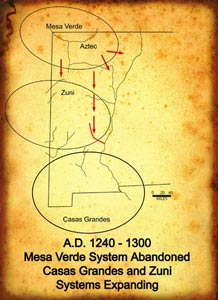

Far to the north a third central place that encompassed the greater Mesa Verde culture area had risen from the ashes of Chaco, but by the beginning of he 13th century, a series of cold wet winters began to force the inhabitants south. During the mid 1200s, one of these northern communities came further south than all the others and planted itself just upstream from the Victorio Site, building Pinnacle on a defensible uplift. Radiocarbon dates strongly suggest that they arrived while Victorio Site was still occupied. Were they neighbors? What required a defensive position? Was it out of habit developed in their old country or were they not welcome? We are not sure, but like the connections between the Socorro and Mimbres affiliates a century before, there is currently little evidence to interpret the dynamics.

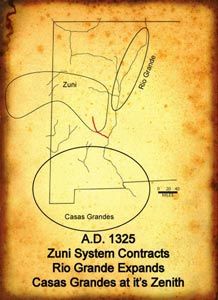

By 1300 the Victorio Site was no longer occupied while Pinnacle Ruin remained a viable, thriving community. In other areas of the Tularosa region, sites like Victorio were abandoned and there was a general retreat toward Zuni. The Victorio Site population either joined this movement or was incorporated by the newcomers whose carbon paint tradition was soon extinguished in favor of the Zuni glaze ware sequence. Thus, both populations had become a part of the Zuni system by the middle 1300s. Simultaneously, populations to the south, including many that must have been Mimbres descendents were thoroughly enmeshed in a system revolving around the prosperous trading center of Casas Grandes. There is little material evidence that this extensive southern trade network of large adobe pueblos interacted to any great extent with the Zuni system. By 1400, the Cañada Alamosa was abandoned by pueblo populations and its long sequence as a pueblo frontier came to an end.

When considering the data from the Cañada Alamosa Project, it may be useful to utilize a world systems approach even though the American Southwest was certainly not a world system in the classic sense. However the basic concept of viewing boundaries as intersections of adjacent core areas and peripheries is generally applicable to the Cañada Alamosa situation. Viewed in the context of world system analysis, the Cañada Alamosa is a frontier as it contains clear evidence of cyclic expansion and contraction from two adjacent centers. Chase-Dunn and Hall clearly state that world systems pulsate, expanding and contracting in cycles and Butzer observes that "the presence of cycles, no matter how crude, is evidence that there is a system." The cyclic nature of occupation and reoccupation of the canyon not withstanding, it is also clear that the cycles visible in its archaeological record do not reflect master plans or centrist plots to further the ends of empire. Instead we see small groups, perhaps extended families or clans, each trying to survive as horticulturalists and/or gatherers in a harsh and varied environment. At times, environmental conditions must have limited or prevented population in canyon. Even with permanent water in the canyon bottom, the plant and animal data from the sites makes it clear that the villages depended on upland resources that were affected by drought. Another limiting factor was flooding, when water from the upper catchment was channeled into the canyon, scouring arable land on the canyon bottom. These periods of depopulation would have served to provide the local environment time for rejuvenation and left the area open periodically to become a region of refuge from the happenings in the central places. What is also clear is that each group was tethered to their central place by the security offered by trade, kinship and social ties. That this dependence was never really broken is evidenced by the lack of indigenous development of ceramic or architectural style (no Truth or Consequences B/W). Instead, outside central places maintained their hold even when the populations moved away from them, probably because old ties of kinship remained strong. Or perhaps other factors, not observable in the archaeological record, held their allegiance. For example, the availability of salt from the Zuni area provides an example of a single important product that would keep a group connected to a central place.

• The Cañada Alamosa Project: Introduction• The Cañada Alamosa Project: Before A.D. 1400: The Pueblo History of the Canyon

• The Cañada Alamosa Project: The Post Pueblo Period: After A.D. 1400

• The Archaeological Sites at Cañada Alamosa

• The Cañada Alamosa Project: Current Interpretations

• Location of The Rio Alamosa : Map